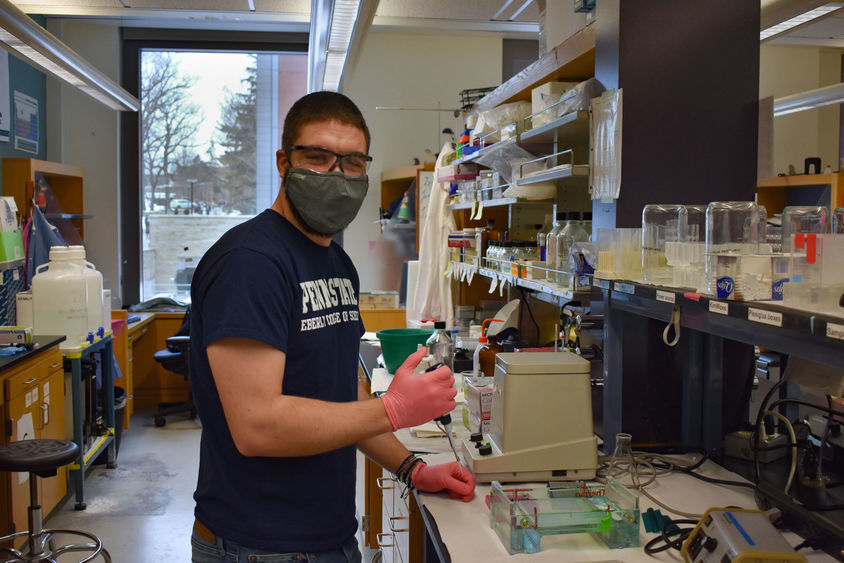

Chemistry major Matthew Herne assess how typical methods to study RNA might be improved.

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — For some aspiring undergraduates, the question of where to attend college is a no-brainer. One chemistry major, Matthew Herne, knew from the start that he wanted to attend Penn State.

“I’m from a Penn State family,” Herne said. “This is basically me living my dream right now — enjoying my time here, meeting all these great people, and having fun with it.”

Herne began his undergraduate career at Penn State Scranton, which provided a solid foundation before he transferred to Penn State's University Park campus in fall 2021.

“I enjoyed my time there a lot,” he said. “Penn State Scranton was great in that it felt like my professors really got to know me from the start. I felt well prepared for my time here. The professors at both campuses have been great about helping out in any way they can.”

In addition to his course work, Herne conducts research in the lab of Philip Bevilacqua, distinguished professor of chemistry and of biochemistry and molecular biology. The Bevilacqua lab includes students from chemistry and biology backgrounds and focuses primarily on studying RNA, a complex, single-stranded molecule similar to DNA. Special variations of RNA are used in our bodies to complete many important tasks, including carrying genetic instructions for creating proteins. Its many functions lead scientists to believe that RNA may have been crucial to the origins of life on Earth.

Structurally, RNA consists of a phosphate backbone and subunits called nucleotides. We know RNA nucleotides as AUCG; the U replaces the T in the alphabet of DNA. Although RNA is a linear molecule, it can fold on to itself to form complex three-dimensional structures, and the nucleotides can be paired up in certain sections like double-stranded DNA. To learn about this 3D structure of RNA, scientists typically use a molecule called dimethyl sulfate (DMS) as a probe, which only binds to unpaired nucleotides. DMS has been the gold standard in the field, but the Bevilacqua lab has been studying a potential flaw with this DMS probe.

“We think that DMS is possibly degrading the RNA by attacking the phosphate backbone in addition to the unpaired nucleotides,” Herne said. This issue can occur at higher DMS concentrations, according to Katie Douds, Herne’s graduate student mentor.

“Matthew's project is to characterize the chemical mechanism of this DMS-stimulated RNA degradation in the hopes that we can either mitigate this issue in our structure-probing experiments or use it as a new tool to learn about accessibility of the backbone,” she said.

Because DMS is so commonly used, this work could have important implications for understanding how RNA is regulated in a variety of species. It may also impact how scientists study the regulation of RNA viruses such as HIV and SARS-CoV-2.

“If it isn’t making the modifications we need consistently, we need to know why,” Herne said.

Undergraduate research was not on Herne’s radar when he started at Penn State Scranton.

“I went to a summer program and met with juniors and seniors presenting their work,” he said. “They said they had a fun time with undergrad research, so I looked into it. I got connected with Dr. Bevilacqua, and I’ve been having a really fun time with this. I’m really glad I did it.”

He hopes to return to Penn State for a master’s degree upon graduation, but he has not ruled out other nearby programs in organic and analytical chemistry.

Herne also acknowledged that his excellent mentors and instructors along the way have made an impact on his research interests. His favorite course at Penn State Scranton was organic chemistry lab with Associate Professor Phuong-Truc Pham, who studies organic molecules with biological activity.

“I enjoyed the processes and the fact that it always just made sense. She really made it enjoyable,” Herne said.

Even with only one semester under his belt at University Park, Herne has already discovered another favorite in his analytical chemistry class with Dan Sykes, teaching professor and director of analytical laboratory instruction.

“He has great stories and is just great at explaining the concepts,” Herne said. “It’s a massive amount of work, but he makes it worth it. The professors I’ve interacted with so far at University Park and Scranton have been so enthusiastic about helping me learn.”

This semester, Herne hopes to continue his research project by using more accurate techniques. This will allow him to gather additional details about the mechanism by which DMS interacts with RNA.

“The experience has made me realize that I really like being in the lab,” he said. “I don’t want to be just writing papers behind a desk. It’s been fun working to understand both the chemistry and biology parts of this project, and I am excited to see where it goes.”